I have successfully turned artistic inspiration into an object which can be purchased!

Plus: If you moved away from San Francisco and *didn't* write an essay about it, did you ever really live there at all?

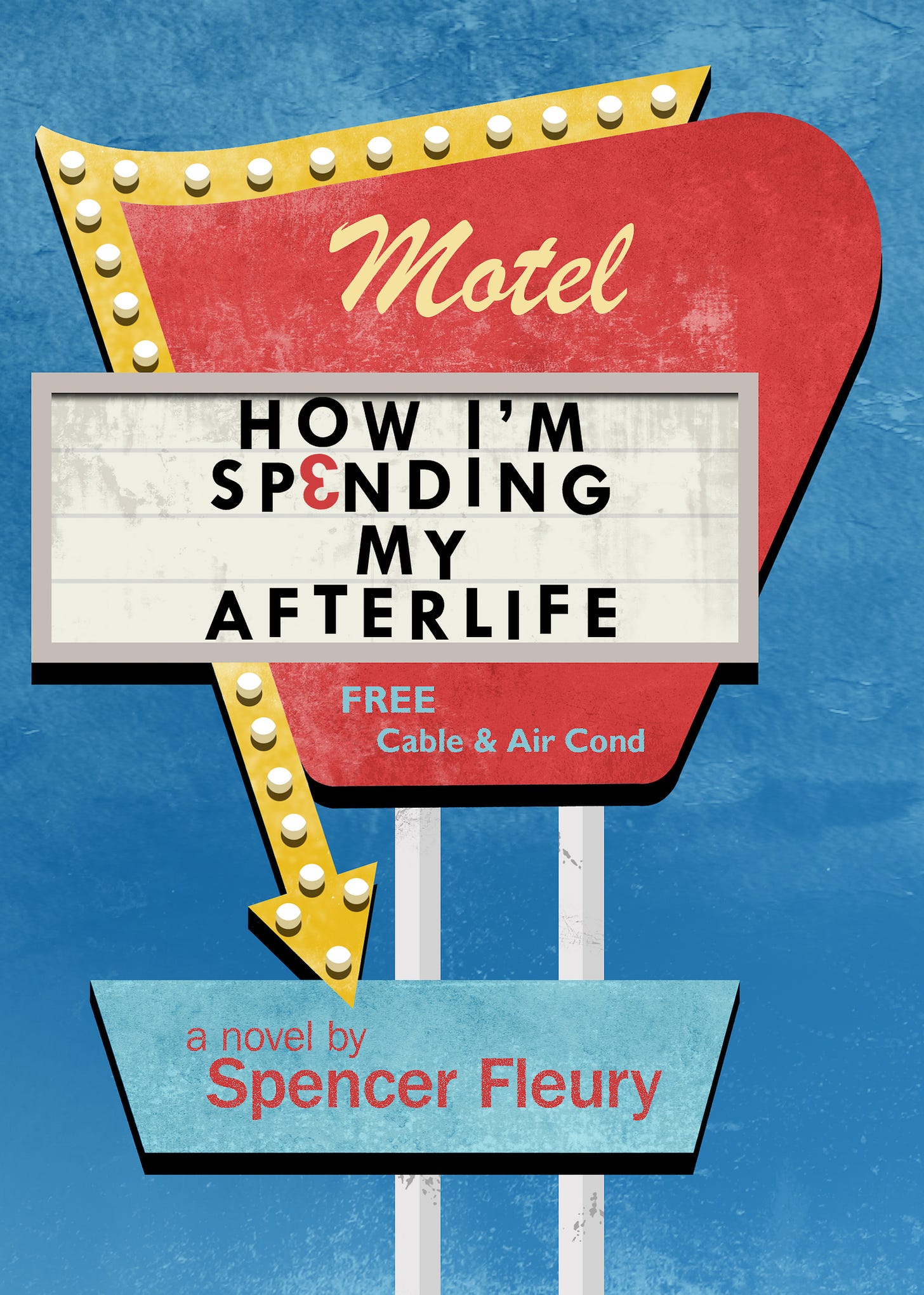

Hello, and welcome to Issue #3 of this newsletter! First, some big news, which you probably already know but maybe you don’t: my debut novel, How I’m Spending My Afterlife, was published by Woodhall Press on Tuesday! (Well, okay, maybe “re-published” is more accurate, but let’s not bicker and argue about who killed who.)

I’ve been doing a lot of promotional stuff to support the launch, including appearing on podcasts as a guest, which is a strange experience. The first one, Ben Tanzer’s This Podcast Will Change Your Life, is already up. I also spoke to Hypertext Magazine about unlikeable protagonists in fiction, sat for an interview with LitReactor, and talked about my favorite coffee mug on the Mugshot Writers Instagram account. There are a few other things that haven’t gone live yet—hopefully I’ll have more links for you next month.

Random anecdote: The time I saw Dick Vitale in a parking lot

If you don't know who Dick Vitale is, I envy you. He used to be a basketball-talking guy on the teevee box. He's retired now (at least, I think he is; I don't watch a lot of basketball) but back in the day—by which I mean the 1990s, in particular the years when I was in college and FSU was demonstrating an uncharacteristic level of competence in basketball, so we all watched it—Vitale was college hoops personified. He was everywhere. He was loaded full of catch-phrases like "it's awesome baby!" and "diaper dandies" (his term for promising young players, one which never failed to get the bile rising in the back of my throat) and countless others. And my god, he was annoying.

As a writer, I feel like I should be able to describe Vitale's voice and style, but I don't think mere adjectives—shrill, grating, piercing, juvenile—can fully do it justice. I think it's something you should experience for yourself.

At the time, Dick Vitale was everything I hated about the 1990s rolled up into an omnipresent flesh sack. He was overexposed, pointlessly loud, seemingly lacking in self-awareness, and completely content-free. And worst of all, he loved Duke University basketball. Fucking loved it, to the point where I began to strongly suspect he made his wife wear Christian Laettner and Grant Hill jerseys to bed once or twice a week.

That said, he never claimed to be more than he was, which was a basketball fan who loved his job talking about basketball. I can't fault a person for loving their work. And by all accounts he's a decent actual human being. He's got a long history of charity work, and when I lived in Florida (he lived there too) I'd regularly see news stories about him getting involved in the community in some way or another. So, not a bad person, but an extremely annoying personality.

In the early 2000s, I was working for a software company in Sarasota, Florida. Our offices were on Siesta Key, a stunning little spit of bone-white sand and gently-swaying palms and rich Republican retirees. In other words, exactly the kind of place that would appeal to someone like New Jersey-born Dick Vitale.

One afternoon I took a stroll down to the convenience store a couple of blocks away to pick up an Arizona iced tea, which I used to do whenever I couldn't stand being in my office for another second. I was rolling some work-related irritation over in my mind as I approached the parking lot when a candy-apple red Mercedes convertible cut me off and shot into an empty spot right in front of the store.

"He almost hit me," I remember thinking. "What a prick."

The driver was standard-issue Siesta Key archetype: old, male, kind of scrawny, wearing a matching royal blue outfit of polo shirt and tennis shorts, sunglasses, and a white ball cap that looked like the sort that would have a country club or a yacht club logo on the front. Without even turning off the engine, he threw open the driver's side door and dialed a number on his car phone (this was long before you could link a smartphone to your car's sound system). I could hear the phone ring on the other end, mostly because the stereo speakers were cranked as high as they could probably go.

"Hello?" a male voice on the other end said.

"Hey Tommy, how are you," said the man in a near-shout, which he amped up for his next sentence: "It's DICK VITALE."

How about that, I thought. Celebrity sighting. You didn't get many of those in that part of Florida. I took a closer look: yep, definitely him, though I never would have noticed, let alone recognized, him if he hadn't said his own name so goddamn loud.

"Oh!" The voice on the other end of the line seemed genuinely surprised to hear from him. "Um, hi, Dick! What can I do for you?"

I went into the store, where I could hear the rest of their conversation as clearly as if I'd stayed outside. I've forgotten the specifics, other than it seemed to consist of nothing more than the two of them exchanging pleasantries back and forth for a few minutes. Then he hung up, finally turned off his car, and came into the store.

"Holy shit, Dick Vitale!" yelled the other customer. He was either a beach bum or someone working a construction job on the island—it could be tough to tell the two apart sometimes—and was pouring himself a gigantic fountain soda. He had a greasy brown mullet, a mustache and a cigarette tucked behind his right ear. "Love your work, sir!"

"Heyyyy, thank you, thank you," Dick shot back instantly. "Love being out here, talking to the people, hearing from the fans. Great to meet you."

And then he left. Without even buying anything.

It was pretty uneventful, as encounters with famous people go, but it stuck with me for one reason: he was clearly hoping to be spotted—otherwise, why make such a loud, public phone call in which he announced his name to anyone in earshot—which is why I was so puzzled that he'd first go to the trouble of hiding his face under that big hat and behind those wraparound shades.

And did he really have nothing better to do than drive around Sarasota all day trying to get people to recognize and fawn over him? I mean, there's SO MUCH golf around there. Surely he could have gotten a tee time somewhere.

Meh. Famous people are weird.

What I’ve been reading

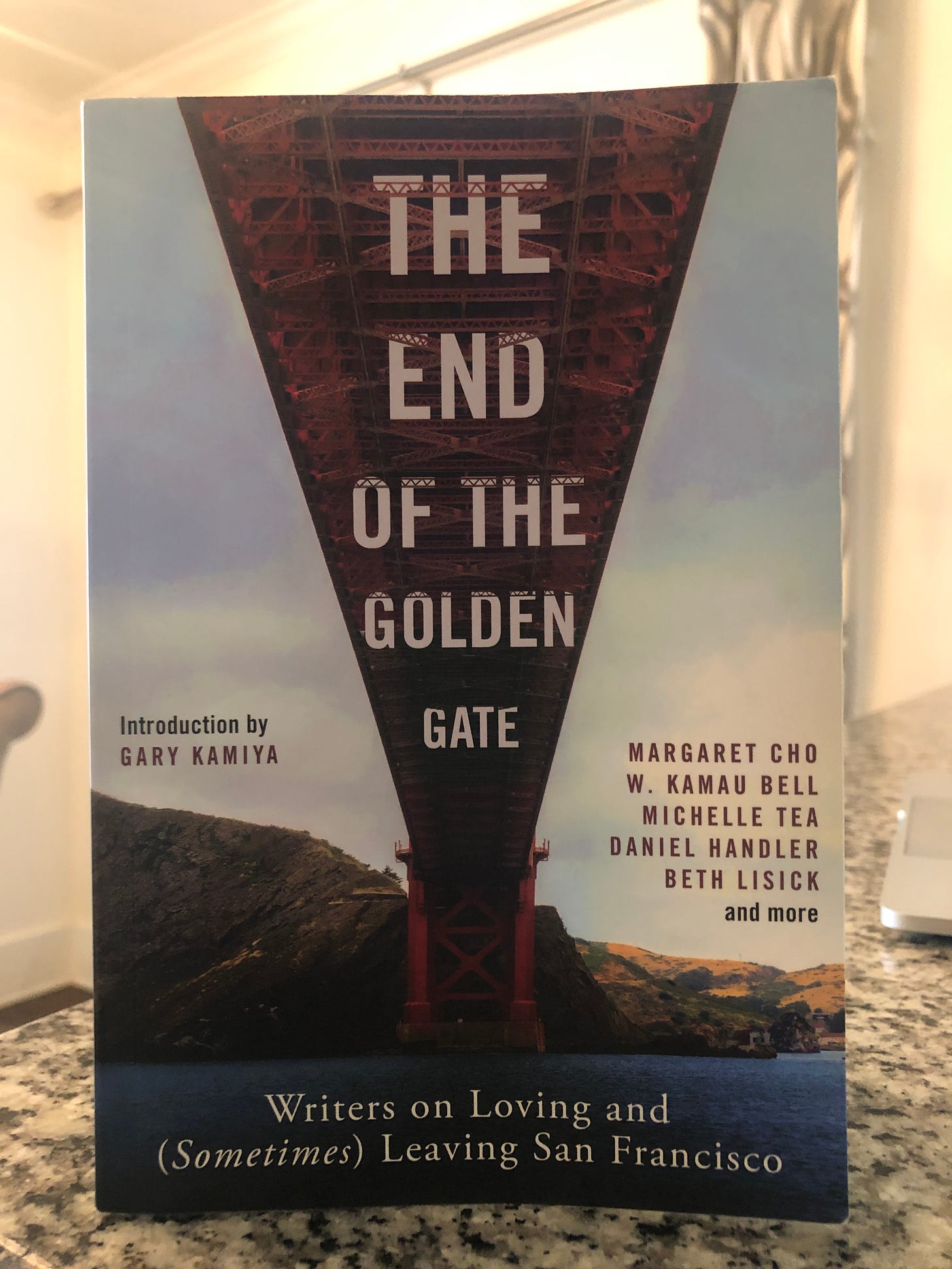

The End of the Golden Gate, with an introduction by Gary Kamiya

This anthology features pieces from writers like Michelle Tea, Margaret Cho, Grant Faulkner, Daniel Handler, and W. Kamau Bell, each with its own slant on this wonderful and frustrating city I call home. For better or worse, San Francisco occupies a unique place in our national imagination. People come here from all over, for all kinds of reasons, and often when they’re young and impressionable. Change here is a given, maybe more so than in most other cities—I’ve only been here for seven years, and I could spend most of an afternoon listing the ways in which the place has changed in just that time.

Whether you’re born here or you’ve landed here, it’s very common to latch onto a specific fragment of your own time in this city and use it as your own personal yardstick for Peak San Francisco, which is the moment the city was indisputably the best it has been or ever will be. If you’re a certain kind of person, you may eventually find yourself spending most of your waking hours fixated on the myriad ways San Francisco has let you down, simply by becoming something other than it was when you got here.

For a while a few years back, there was a whole cottage industry of writers leaving San Francisco and publishing a piece in Medium or The SFist or 7x7 or The Bold Italic, in which they worked a little too hard to convince whoever happened to be reading that leaving was the right call; that San Francisco was dead, done, over; that anyone who had any sense or who wasn’t a total lamestain would surely be following suit. It always felt to me like they were trying to convince themselves more than anyone else.

I almost didn’t get past the first four or five essays in this collection because they were too reminiscent of those tedious pieces. “But nothing is there anymore, she said, and it’s true,” writes Michelle Tea. “Nothing is there.” But the very next paragraph begins with a list of things that are, in fact, still there: Outerlands, the windmills in Golden Gate Park, ice cream from Bi-Rite, the “gloomy zoo.” But that’s the thing about most essays in this genre. They’re not really about the city at all—they’re about the writer, how they’ve changed. Don’t get me wrong: those can be fascinating reading. But as an unapologetic San Francisco cheerleader, I guess I just bristle at the framing.

That said, there are some great reads in this collection: Kimberley Reyes’ description of experiencing San Francisco as a Black person (who make up only 6% of the city’s population), Fayette Hauser’s vivid recollection of the old Russian Embassy and the city’s 1960s counterculture, and Duffy Jennings’ piece on working as a journalist through some of the city’s more turbulent times all stand out. More than anything else, this collection illustrates how San Francisco means something different to everyone who’s ever lived here. It’s a symbol as well as a city, and the meaning of that symbol can be so personal that it becomes impossible to separate it from ourselves.

Thoughts on writing: On being a late bloomer

I got a late start writing fiction.

It's something I always wanted to do, at least going back to when I was nine or ten. That summer, I got it in my head to write a story, a Friday the 13th-style slasher story about a maniac named Clay who killed off summer campers (modeled on kids I knew from Roper Day Camp in suburban Detroit) until meeting his own violent end, which I think was electrocution-based.

I had fun writing it, but writing fiction didn't stick then. I put it aside until I was in high school, working in a library and reading books like The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and Less Than Zero and Skeleton Crew (Stephen King’s short fiction has always been better than his novels, in my opinion) and, because I was an angsty teenage boy, Catcher in the Rye. These books inspired me to try again; I can do this too, I thought.

So I wrote. I wrote through my senior year of high school, my college years, my first couple years in the Coast Guard (that's when I also started trying to write screenplays, having seen Reservoir Dogs and Glengarry Glen Ross just before I graduated college). What I didn't do is take a single creative writing class. I don't say that to brag, because looking back, I think it was a mistake. At the time, I had the stupid idea that writing wasn’t a talent you could develop in a classroom setting—you either had it, or you didn’t, and the only way to improve was to just keep at it.

The problem with this approach was that I hated everything I wrote. Everything. What seemed brilliant in the moment read like pretentious auto-fellation the next day. Every line of fiction I wrote ended up mortifying me.

But I was good enough to write other things. Ad copy. Record reviews. Software manuals. Magazine articles. Scripts. A three-hundred-page dissertation on land use policy in environmentally-sensitive landscapes (yeah, don't bother with that one). Everything but fiction.

I had no style. And I had no idea how to develop it. I began to accept that I would never write novels or publish short story collections.

But it was more than that, and when I was in a particularly reflective mood I could articulate the real reason I wasn't writing fiction: I didn't think I had anything worth saying.

Successful fiction, the best fiction, the kind of fiction that endures, has the ability to show us truths about ourselves and the world around us that we wouldn't otherwise see. And certainly I had stories I could tell, life experiences that lent themselves to narrative. I'm doing that right now, in fact, with my second novel, which is based on my experiences in the US Coast Guard in the mid-1990s. I recognized a long time ago that I had the makings for a novel in my experiences during those four years of my life. But I had no idea what any of it meant, or more to the point, what any of it could or should or would mean to anyone else.

I've been carrying those experiences around with me for more than twenty years now; it took me most of that time to really understand them, to see what they revealed to me about the world, about other people, about myself. And it took me even longer to decide that I was able to express that understanding through fiction, through stories, through my own creative process. Hell, I didn't get there until after I turned 40.

So I started to read writing books, on technique, approach, mindset, whatever. Most of them didn't help. Then finally, one of them did: David Morrell's The Successful Novelist. I focused on a few specific technical suggestions and applied them to the first eight pages of an idea I'd had in my head for a few years. Then I put those pages in a drawer and forgot about them for a few more years. Then I found them, discovered to my surprise that they weren't so bad, and decided to finish the book, even though I didn't know how it was going to end (something I plan to talk about in a future issue). The result was How I'm Spending My Afterlife, which took me two years and change to write and which, after a long and circuitous journey, is finally a for-real published novel, thanks to the good people at Woodhall Press.

I'm not trying to justify my late start in this newsletter. For one thing, I don't need anyone's permission for or approval of the path my life has taken. More important than that, I don't think starting late requires justification.

But.

I've heard it said that you shouldn't try to measure your own progress in life against anyone else's. That's great in theory but is nearly impossible to put into practice. It's just human nature to look at someone else, someone who has achieved the success and status that you crave for yourself, and wonder what the hell is wrong with you that you're lagging so far behind.

A lot of writers who have a career trajectory I hope to achieve one day are younger than me, sometimes a lot younger. It's dispiriting sometimes. I sometimes feel like I could have already made it big by now, or at least respectably, if only I'd started sooner.

But would I have? If I wasn't ready to write, I wasn't ready to write. Yes, starting late was almost certainly a disadvantage from the perspective of building a real career out of writing fiction, assuming that's even possible to do anymore. But it just as easily may have been the only way for me to do this at all. If I'd started too soon, before I was confident that I had anything to say, what would that have looked like? I mean, I remember some of the novels I planned to write, back when I was in college and before I knew the first goddamn thing about anything. They were formless, plot-driven, thinly-conceived. If I'd written those under my own name, I'd be calling myself Steve Bennett by now.

I think I did myself a big favor, honestly. I may have lost 20 years of back catalog, but I think the odds are good that I'm much more likely to remain proud of my work for years to come.

That’s all I got for this month. What’s on tap for next month? Check back then and we’ll find out together!

And if you enjoyed this newsletter, I’d certainly appreciate it if you’d pass it along to someone else who might dig it. Thanks!